Searching the scientific literature#

Word count: 0 words

Reading Time: 0 minutes

Half a million academic papers in chemistry are published each year and there is about 200 years of excellent scientific precedent for you to become aquainted with as well.[1] Where do we begin to take on such a daunting task?

A few tips to get you started#

A literature search is rarely a straight line pointing but a sprawling network of interconnected articles, books, people, and communities. Each with their own motivations, interests, vernacular, and empirical standards. The only way to learn how to effectively navigate these streets is to walk around, read, talk to your friends, and if you get lost ask an expert for directions.

1 | Develop a clear and focused research question or hypothesis.#

This is easy at the surface but almost always evolves as you read and learn quite a bit about your topic before the questions that need answering of the story you want to tell becomes apparent. Your first questions are usually not very good. Often it is too vague or general to respond to clearly or they’ve already been answered by someone else. So you revise the question to be more specific or you better defined the important limits of the communities understanding or a topic. Read some more and repeat.

2 | Use tools to aid your search for the best sources#

There is no single tool for searching the literature and preferences are different for everyone. Google scholar is a great resource. It’s fast and easy to access for free. However, if you’re just getting into a field you can be overwhelmed by the overly specific results populate the top hits. Google Scholar’s top hits are based on relevance you the keywords you typed into the search bar. If you’re just getting started then what you’re probably looking for are books, review articles, and perspectives that give a broader overview of the field. Filter your google searches to include only these results. For review articles specifically Google Scholar has a button on the left side of the screen that attempts to filter only for review articles. However this will often miss reviews in journals that are not specifically labeled as such and will also miss books and prespectives.

An alternative option is to just read through the results and keep an eye out for key articles. There are usually context clues indicating which are books and reviews. Google Scholar also attempt to quantify how many other publications have cited a given article. Citations are a rough metric of influence and academia and articles with many citations have clearly already been read by many other people. This is usually a good place to start. Beware, articles with the most citations are not always the best or most accurate, or “most important”. Overtime you’ll learn to evaluate quality by reading the articles themselves. Obviously, new publications have no citations and yet over time they may become the most important. This may happen rapidly in a fast moving fields or take decades to gain the recognition they deserve.

Web of Science is another great search tool with better curated and more complete information than Google Scholar can provide. There are only half a dozen major publishers of journal articles in chemistry: AAAS, Springer, Cell, American Chemical Society, Royal Society of Chemistry, Wiley, and Elsevier. If you’re looking for good peer reviewed journal articles to help introduce you to a field it will likely be from one of these publishers and usually in one of their more prominent journals. Some of the most interesting topics may only have a few people publishing in which case you may need to consider more specialized journals centered around a small but active community. These can also be quite good.

Beware of papermills. These are journals that publish just about anything for a fee or collude with authors to publish and self-cite their own work. These are not reputable sources and should be avoided. Remember the articles and journals of science ware edited and written by real people whose reputations can be easily checked with a few simple web searches. When in doubt, look up the authors and the journal editors to learn more about whose work your reading.

3 | Track down a high quality book or review article early#

You may not need to read the whole thing. Often if you’re just getting into a field the introduction will provide more than enough detail for your current understanding of the field. You can return and read the more specific sections as you’re experience with the topic grows. In more technical books the first chapter or two will ofter cover basic fundamentals before diving into the more specific (and perhaps less relevant) details in later chapters.

4 | Use keywords and filters to refine search results.#

Once you have some familiarity with the research area and know where to look you should know what keywords are worth searching for. Refine your search engine results further with more relevant, accurate, and precise keywords.

5 | Keep track of your sources and take notes.#

Keep a list of all you citations in a place where you can add notes or take screen shots of key passages and figures. There are many way’s to do this. You can simply print out the articles and keep a paper notebook of your thoughts on each paper, or you can use a notes app to keep citations + personal notes + screenshots. Or you can keep a folder of pdf documents along with a text file or word document that contains all your notes. They choice is yours. It doesn’t really matter how keep notes. Just pick a method and be consistent.

An example search#

Let’s search for information about our chosen topic: uranium extraction for seawater. The first place many of us would go first is probably the wikipedia page for Uranium. Wikipedia is not necessarily a reliable source based on academic standards considering the existing editors and peer reviewers are not curated by a professional editorial staff to qualify their expertise. Nonetheless from experience most of us I think have found the information here to be more or less accurate a lot of the time. Just understand that Wikipedia is the start not the end of our search.

On the Uranium page there is a section here on “Resources and Reserves” with a bunch of citations. We’re interested in sea water so we’ll skip to that paragraph. It turns out are some good and a lot of bad citations here. We’ll focus on those that are peer review work, and printed works by renowned authors. If you hover over the citations you’ll get the reference. The one shown is the only peer review article that is cited, Fig. 40. It is old and weirdly specific. This is a bad citation for such a general article. Surely a more recent peer-reviewed review article on the field would be more appropriate. But this is a starting point.

Fig. 40 Section of the wikipedia page “Uranium”. Hover over the references (e.g. [90]) to see what is cited.#

There are a lot of low quality references on Wikipedia (publications that are not peer reviewed or disreputable, random websites, blog posts, new articles…). Be careful. Even those from reputable sources like this one are not very relevant to the discussion topic. It appears that this is the best experiment for extracting uranium from sea water. It is not! There are many papers describing similar experiments. Wikipedia should probably have a few more recent review articles cited here instead.

Reading the primary literature#

Let’s open the article. It turns out to be short but then introduction does introduce the general process they are using which could be valuable information. Let skip to the good part though. The citations! Luckily our job is easy because this journal had the good sense to include titles in the reference section. If there are not titles then would could easily triangulate the reference we wanted by reading the first few paragraphs of the introduction. It is usually (but not always) where broad scoped review articles are cited. In the footnoote we see an old (published in 1980) but potentially promising review article on the topic, Fig. 41. This is a good place to start.

Fig. 41 The references are at the bottom of the article that we found a link to on wikipedia. This first one looks like is has a pretty general title and may be an overview of the topic. Next let’s find this by going to google scholar.#

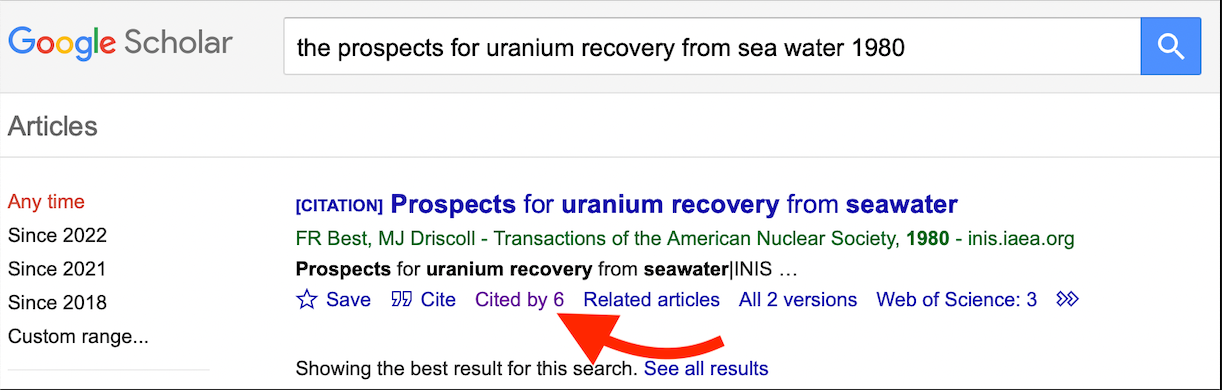

Copy and past the title into google scholar will very often results in the top hit being the article you’re looking for. This is the case here, Fig. 42.

The best feature of google scholar is the “cited” button and the “Web of Science” button. The Web of Science is a higher quality tool for searching through a papers citations and for papers that cite the current paper you are viewing. The “Cited” button is pretty good though too and it’s what I often use for initial literature reviews. It looks like not very many people cited this. Either people had a difficult time accessing it (diamond in the rough?) or it’s not the best reference. I would recommend reading this one to find out the state of the art in 1980. Sometimes these older reviews are also better at providing an accessible overview of the field.

Let’s click the cited button. It looks like since this article was published Google Scholar has found 6 other articles that cite this one. Here we can imagine that we are moving into the future from our starting review article getting a list or related but more recent publications.

Fig. 42 Google Scholar search results. This item matches the citation above so we found what we were looking for. Google scholar gets easily confused by punctuation marks and special formatting (like chemical formulas) I usually remove all this information when searching for a specific citation on Google Scholar. Including author names can also help, but I recommend only including a few of the last names separated by spaces.#

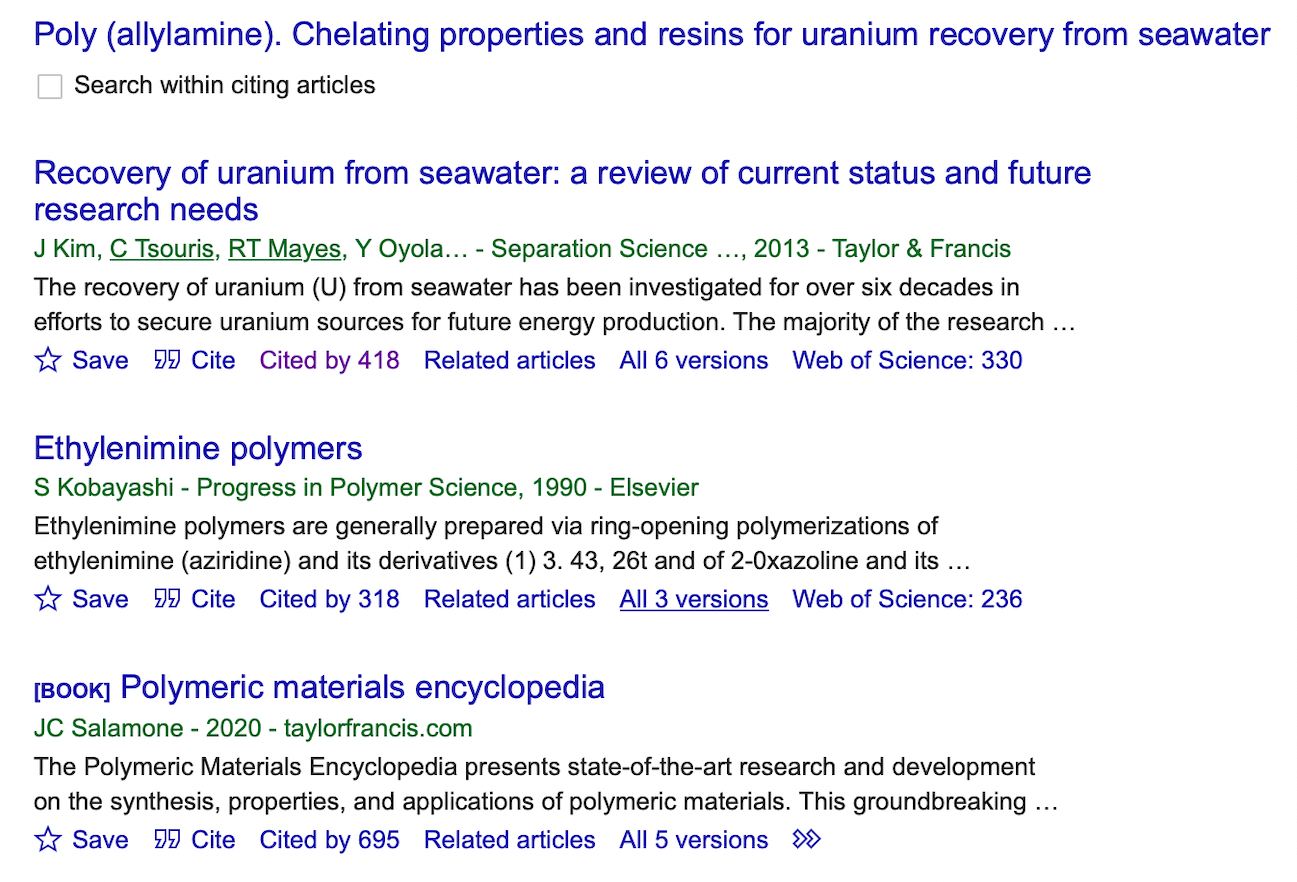

From the list of articles that cited the original article we again appear to get a few reviews but they are more specific in their focus. As we more forward in time we are now in the mid 1980’s and these articles are more highly cited.

Fig. 43 Google results for the articles citing “Prospects for uranium recovery from seawater”.#

Right now we’re interested in working our way through the tree of citations. So let’s keep clicking the “Cited by” button on the more popular articles. A good paper will probably have a few dozen to citations. I don’t see a good review article here. Let’s click the cited by button again!

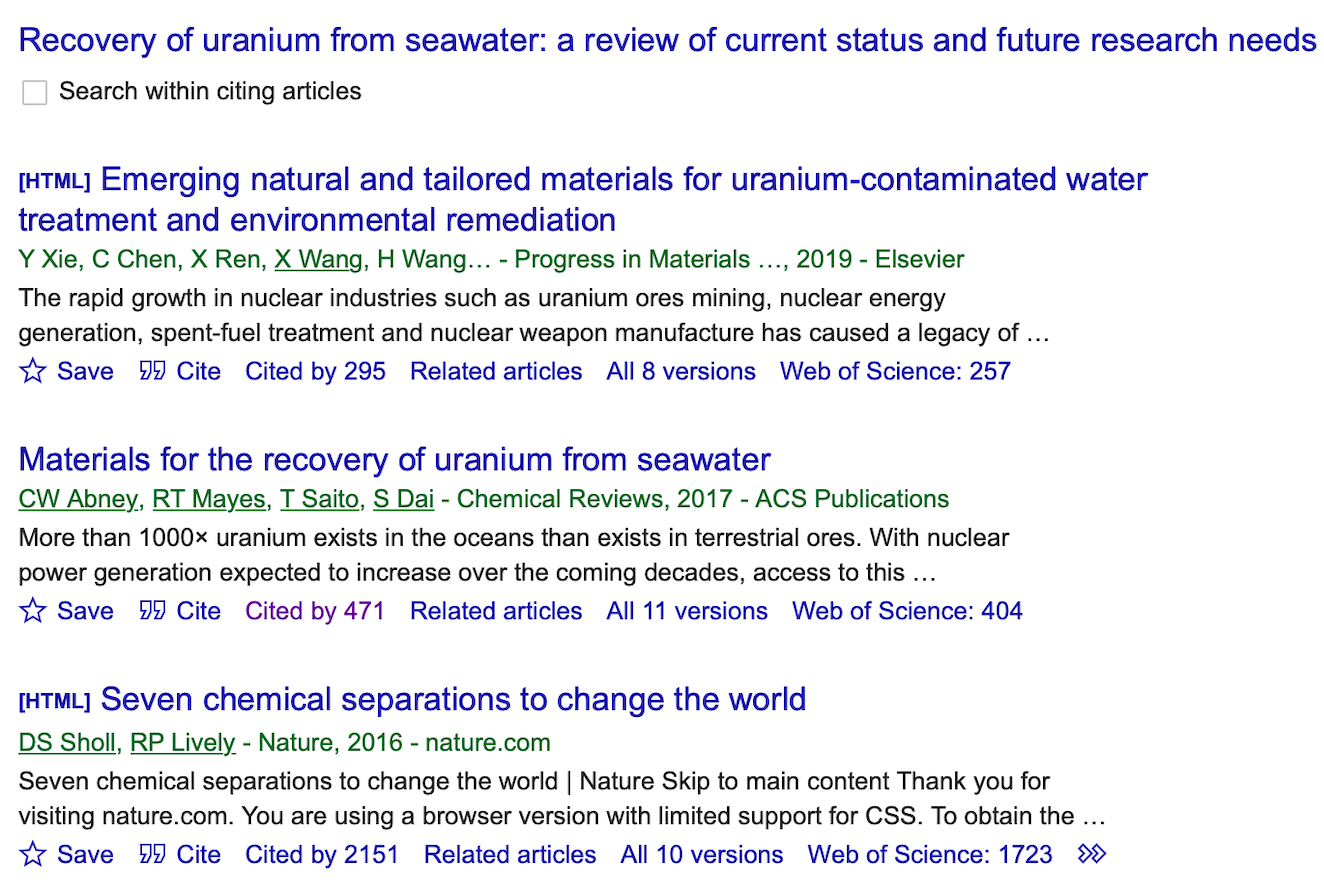

Fig. 44 Finally a review article on getting uranium from sea water! Why didn’t wikipedia just cite this one?#

The top results looks good now, but it’s from 2013. This is probably good enough for getting us a good introduction to the topic. It might be the best. But let’s click the button one more time to see if there is something more recent.

Fig. 45 Here we find a Chemical Review from 2017. Chemical Review is the top journal in chemistry for the publication of very comprehensive review articles. This is a really good source.#

In Fig. 45 the title for the second looks a bit more specific than the previous one but Chem. Rev. articles can be quite lengthy and it could likely cover just as much if not than the the other ones we’ve found so far. It is also more up to date 2017 vs 2013. We could keep going but we now have located two articles worth reading after just a few minutes of searching. The third article on this list is very broad in published in Nature perhaps the most influential journal in science. This may also have a good overview within it amongst a lot of other topics we’re not interested in right now. This too could be a good source.

“Cited by” moves towards the future. We started with in article from 1984 and pulled a reference from it from 1980. Using the “cited by” Button we then moved forward in time up to 2017.

Web of Science helps you travel into the past. Let’s take the Chem. Rev. article from 2017 and click the Web of Science Button, Fig. 46. First the main list will look pretty similar to what is on google scholar. But Web of Science also has in the right panel a list of articles that this article cited. This is a great way to move backwards in time.

Fig. 46 Search web of science for “Materials for the Recovery of Uranium from Seawater” and you’ll find this page as one of the top hits. On the right a column labeled “Citation Network” The “265 Cited Refereces” link on the right is the button that lets us travel into the past. Let’s click that one.#

Now we’ve found a large portion of the good stuff. This review (and by tracing its citations back in time) we can start to map out all the major advancements from the dawn of science up to 2017 relevant to extracting uranium from seawater. With a more rigorous search based on multiple points of entry into the academic record of citations we can begin to exhaustively identify every every research group and every major advancement in the field over its history.